Bab-el-Wad

Concrete, rubber, pencil on paper, 2017

Authenticity is a fascinating but problematic concept, the philosophical question of the origin and its copies is an enduring one.

The process of making this work mimics the story of the Bab-el-Wad monument: the original wrecks of vehicles were rejected by the monument commissioners, so new ones were ‘manufactured’. Similarly, I created two sculptures: First I casted in concrete the impression of an authentic memorial wreath I collected at the Bab-el-Wad Memorial Site. Second, I weaved in my studio a new memorial wreath from fresh flowers, then casted this new wreath in rubber. The rubber wreath’s impression was casted in concrete too, creating now two sculptures: one authentic, the other a copy. A monument occupies a space, declaring ownership of its land. My casts, presented as works of art in a gallery space, become neutralised, independent of their origin.

When the original wreath was wilting in my studio, I took a few flowers out of it as I knew it would be destroyed after the casting. I made moulds of the flowers, to create a new memorial wreath, a reconstruction of repeated concrete flowers from the original one.

The wreath of concrete stands side by side with the fake rubber wreath. They are both lifeless. One is solid and everlasting while the other is elastic and precarious.

Images: Nemo Nonnenmacher

Bab el Wad – This Stone shall be a Witness Unto Us

It was a hot, sunny day in early June. We were driving in a convoy, going up to Jerusalem on Highway No.1. I was driving the leading car; three more cars followed. I had travelled that road many times before, going through the narrow gorge known as Sha’ar Hagay in Hebrew, or as Bab-el-Wad, its original Arabic name, meaning ‘gateway to the valley’. The landscape typically includes wrecks of old rusted, burnt, bullet-punctured armoured vehicles scattered by the side of the road. These wrecks are actually relics from the battle for the road to Jerusalem, one of the major battles of the Israeli War of Independence in 1948, the remains of the convoys that carried supplies and auxiliary staff to besieged Jerusalem. After the war the wrecks were moved to the roadside, not to avoid disturbing the traffic but to remain as silent evidence. The burnt, rusting wrecks became symbolic of the heroic sacrifice of the drivers, mostly civilian volunteers. Shortly after the war, a song was written about Bab-el-Wad, emphasising that the fallen should not be forgotten, comparing the wrecks to the silent fallen comrades:

Bab-el-Wad,

Do remember our names forever,

Convoys broke through, on the way to the city,

Our dead lay on the road edges,

The iron skeleton is silent like my comrade.56

It soon became one of the most popular songs of this period and over the years has gained mythical status. In the national imagination the wrecks were thus rapidly transformed into relics, becoming both an object of pilgrimage and a striking landmark for travellers on their way to the capital.57 On Israel’s tenth Independence Day it was decided to transform those relics into an official memorial, the first memorial commissioned by the Israeli government. After long debate, it was decided that the wrecks would be left as they were, with simple preservation work. The battle dates were engraved on nearby boulders, detracting as little as possible from the authenticity of the wrecks and enhancing the evocative power of the landscape by mobilising natural objects and topographical features as additional primary witnesses.58

The road, which became Highway No. 1, is linked with the relics, endowing the relics with evocative power. It seems as if time has stood still since the date of the battle, even though the relics have been relocated several times over the years due to roadworks. Stopping on this part of the road is forbidden by traffic regulations, so access to the relics is restricted, and can only be managed with great difficulty. As this is a main highway, the relics are seen regularly by travellers to and from Jerusalem. Public interaction with them happens mostly in motion.

In 2009, preservation work was carried out to address the decay of the vehicles: they were painted with anti-rust paint, and were rearranged so that they would be more publicly accessible. It was still difficult to reach them, but theoretically possible. This caused a public debate about the authenticity of the relics and brought to the surface many earlier facts and discussions that had led to the establishment of the memorial sixty years before, when governmental committees were held away from the public eye. Apparently, sixty years earlier the area had been restricted from view for a while so the displacement of the vehicles to the roadside was hidden from passers-by. It was reported that at the time the original vehicles were replaced by new ones. There was proof that ten old ambulances were sold to the state.59 The theory presented was that the original vehicles did not look ‘right’, so similar vehicles were bought, then made to look as if they had been damaged during the war. They were artificially decayed, burnt and shot at. The whereabouts of the original vehicles remained unknown. The State of Israel denies these accusations but this discussion is still active in academic historical circles.

So, back to that hot June day. Earlier, when I mentioned a pilgrimage to Bab-el-Wad, I was made aware that Highway No.1 was again undergoing construction, and that the Bab-el-Wad relics were moved while the work was being carried out. I asked some friends to pay attention to the whereabouts of the relics on their way to Jerusalem. One reported spotting them at the next junction toward Jerusalem. Another said they were moved to the other side of the road. I decided to go and look for them myself. I persuaded some friends to come with their families to have a picnic with me at the memorial. In Israeli culture, The Memorial Day for the Fallen Soldiers is followed by Independence Day; there is a strong link between the two. Ceremonies for the fallen soldiers are held in military cemeteries in the morning, and in the evening of that day the independence celebrations begin. The usual way of celebrating is to have a picnic on the morning of Independence Day.

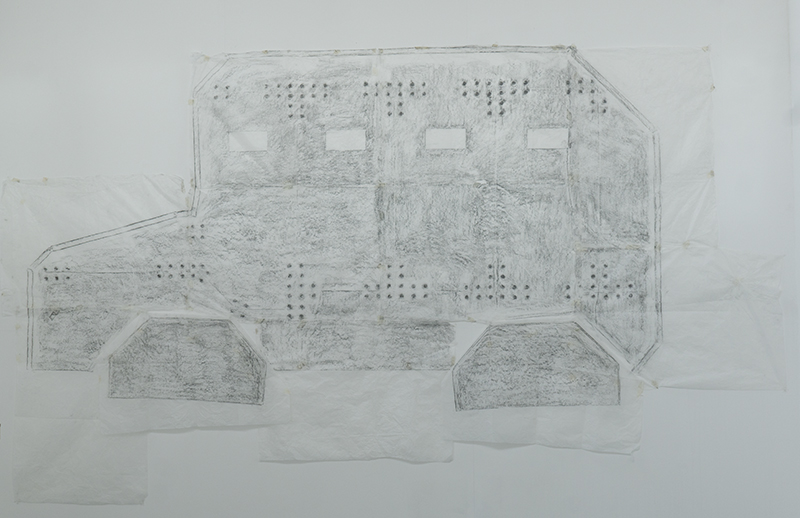

We drove past Sha’ar Hagay, and the next junction ahead, but we saw no relics. We decided to continue looking on the dirt roads going to the woods surrounding Jerusalem. Interestingly we spotted a sign to the Jerusalem Siege Breakers Memorial. We followed the sign and found ourselves in a very strange memorial/picnic site. There was a small memorial for the soldiers of the War of Independence, followed by a couple of flat rusty-looking metal sheets (actually made from a wooden board painted to look like rusty metal) in the shape of the Bab-el-Wad armoured vehicles. On one side was a flat car, and on the other side benches were attached to that ‘car’, making it an armoured car-shaped picnic bench. Nearby were a couple of these odd-looking benches and some regular picnic tables. We parked the cars and started unloading. While my friends and their families were eating, I went to explore the space. I saw remnants of the Memorial Day for the Fallen Soldiers ceremonies held a month earlier – a wilted memorial wreath was placed at the site. I wanted to take the wreath with me but wasn’t sure of the ethics of this; I felt it wasn’t quite right to take a wreath that had been left as a symbol of remembrance for my ‘artistic’ goals, and more importantly would be seen as disrespectful by others, so I left it there for the moment. As I planned to make rubbings of the original relics, I had brought my materials with me. I decided it would be useful to do rubbings of the dummy relics-picnic, especially bearing in mind the whole question of the importance of authenticity in terms of the original memorial. I went ahead with the rubbings, and by the time I had finished, it was time to pack up for home. Just before we left, I stopped the car in front of the small memorial and quietly put the wreath into the boot of the car. There were some other families picnicking at this strange site, and I did not want to raise any questions at that point, but it seemed that having the wreath as research material, having an authentic trace from this site, was an opportunity I could not miss. I packed the wreath in my bag and brought it back with me to London.

I left the wreath to wilt for several months, not sure exactly what to do with it. Finally, I cast it in concrete, trying to create a memorial of my own, casting its absence, its trace. The outcome was not successful at first, but the authentic wreath had been ruined during the casting. I had no choice but to fake a new cast with a fresh new wreath I made on my own. I did this, finally making the memorial I first imagined. Whether it was authentic or original is another matter.